Fighting a pandemic: the power of people and tech (in that order)

16 April 2020

As we continue to make our way through unprecedented times amidst the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak, with Nightingale field hospitals opening all around the country, we spoke to former Lieutenant Colonel Chris Gibson to find out how he used regimented quality assurance and collective training processes to support the fight against the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

In 2014, Chris Gibson MBE held the role of Chief Instructor for the UK Ministry of Defence and led on the development and delivery of a training model for 1,200 UK military personnel and NHS volunteers to combat the Ebola virus in West Africa. Through this role, he was responsible for ensuring that each individual deployed was appropriately trained and equipped for the rigor of delivering care in a West African jungle.

What does UK military training protocol for the delivery of care look like?

Our training programmes were delivered through a collegiate and collaborative process of slow to medium to fast paced delivery. Anything that we held in readiness, anything that we pushed out the door to deliver healthcare on the far shore was six-months in the making through robust training programmes to ensure everyone is as good as they can be within that timeline.

We would start off with establishing the baseline of individuals, ensuring they were fit to operate with the appropriate knowledge, skills and attitude to work in the environment they would be deployed to.

We understood how to work with individual requirements competently before we converged them to operate as teams and then we combined those teams to operate as a complete organisation.

In practice, that meant 250 medics training at any one time for four days solid; with patient flows going in as if they were taking over a capability that was fully operational – which would always the be the case apart from the initial entry operation.

The military really understand how to make a trauma hospital work well – to such an extent that we created the highest survival rates (98.6%) in the history of medicine for those injuries treated at Camp Bastion. For the period we were in Afghanistan, we had created the best (and busiest) trauma hospital in the world.

The most important thing we discovered was that through rapid innovation processes and adoption of lessons learnt, we could improve outcomes exponentially.

How does this differ from normal healthcare professional training?

Our training focussed on collective capability – which is very unusual for training healthcare professionals. The delivery of health and care is a team sport – you wouldn’t normally work in isolation unless perhaps you’re doing research. However, healthcare professionals rarely train as a team.

The military recognised that was something they were good at. We started working out how to build our health capabilities for defence through collective assurance.

How did your involvement in the Ebola outbreak in West Africa (2014-2016) come about?

I had spent several years in Sierra Leone so I knew the country really well. I’d seen it in good times and in turmoil and I knew the terrain. I’d also seen an Ebola outbreak in Kikwit in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in 1995. So, I understood a bit about the disease as well and the impact it would have as a category 4 pathogen within a third world country.

It was the Duke of Wellington that said “if we were not prepared to fight this abroad, we’d better be prepared to fight it at home” and I remember thinking it was absolutely right to get out there and help a Commonwealth country in its time of need.

I knew nothing about infectious diseases, so we had to go back to first principles of what we did know… how to train and assure capability. We turned a lot of things on their heads as the principles of first aid were very different from a trauma teams – namely, ensuring the clinicians and volunteers didn’t become casualties themselves. Instead of multiple hands on a patient in a highly dynamic environment, it was much slower paced so we could work out how to operate safely.

We went from delivering highly effective trauma response to a completely different environment with a different medical delivery to consider. And we did it to such an extent that when assured, we got the highest compliance rating ever given by the World Health Organization (WHO) on the capabilities that we pushed out there.

What lessons can we learn from your experience?

In the military, we talk about three components to an organisation:

- The physical

- The conceptual

- The moral

You can procure all the equipment and create the best environment to get the physical component right. You can have the most focused strategy and a robust set of operating procedures to get the conceptual component right. But the bit that tends to be forgotten, although it’s starting to emerge more now, is the moral component – the wellbeing of your workforce.

I think one of the biggest lessons we learnt through training both military personnel and civilians was the importance of enforcing this moral component – to give those on the front line the confidence to step over the start line in the knowledge that the organisation has their back. If you don’t get that right, they won’t deliver – and why should they? Because they’re scared; because they’re anxious; and they won’t fully engage because that’s human nature.

All three components need equal investment so I think that’s the bit that I would push the hardest, especially just now.

I talk about the moral component because I saw it when I got it wrong – I was so fixed on proving to the chain of command, the Ministry of Defence and Government, that we had created a solution that would work that I negated what that felt for those individuals that I was training to send out. I really had to step back, give myself a serious talking to, go back in and re-align that. It wasn’t about proving to the chain of command; it was about proving to the people that were going out there to deliver that we’d got this right. The rest would follow.

And what part does technology play?

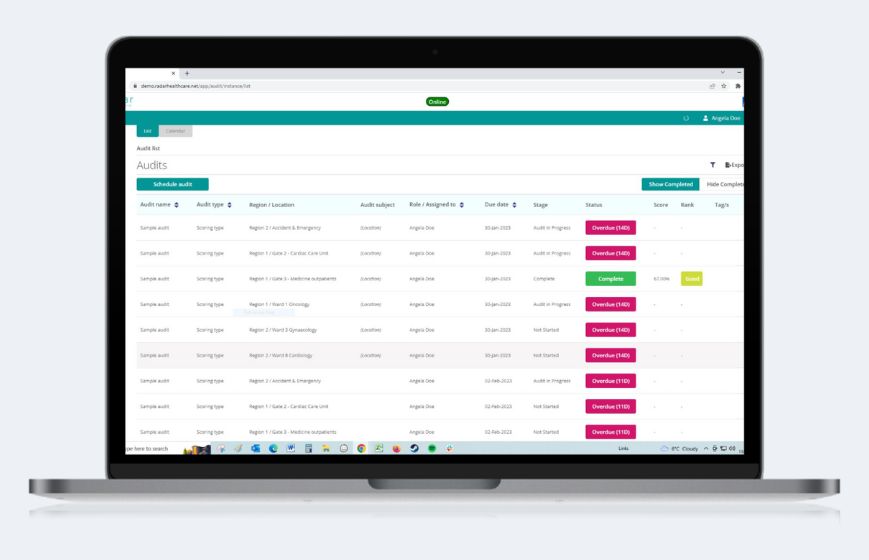

In the field, we created an amazing assurance capability, but it required a lot of manpower to capture data on iPads or manually in notebooks which then needed to be transferred to a massive spreadsheet. Although the data that we were capturing was really vital, useful and pertinent, it wasn’t elegant, it didn’t give us rapid access and it was slowing us down in identifying where risk lay and where strengths needed to be sustained within the deployed hospital’s capability that we were preparing. What we needed was something like Radar Healthcare!

In situations like this, it’s important that data presentation is broken down into key performance indicators and decisive conditions can be analysed to determine what good outcomes mean.

We’re in a kinetic environment just now where rapid decisions are being made and real leadership is required – at the highest level right down to the tactical space where doctors are having to make decisions on how the best care is given. They can only make these decisions based on the information and data they have in front of them; technology can deliver this readily and in an easily digestible format.

There’s going to be some really hard decisions to be made over the coming weeks and months. There are already discussions about when an ‘eligibility for treatment’ matrix may have to used to determine the provision of ventilated care and having the right technology in place to support this decision making will be key.

Are there any positive outcomes you’ve seen during this crisis?

I remain in the military reserve and I’m on the faculty for several NHS Leadership Regional Academies so I’m interested in how we create positive influence when the organisation is working as hard as it can to deliver best effect. The question was always how we get the numbers of trained personnel back into the system if this situation exponentially increases the demand on the healthcare system. And people are coming through.

In its time of need, we see those that retired or stepped out of health volunteering to come back and that’s laudable; it makes me very proud that there’s people within our society that are willing to return to the front line.

How do you think the COVID-19 pandemic will change the healthcare landscape?

My view is that this situation will, in the short term at least, give patients a better understanding of when they need to see a clinician, particularly for minor ailments. We’ve seen a significant decrease in patients presenting in primary and acute care and there are of course combining factors that support this; the activity that would cause trips, slips and falls within the workplace probably isn’t occurring; the motorways and roads where accidents occur are probably much less. But there’s also the notion that people are not presenting because they understand that there’s more risk in doing so than not. And therefore, they’re choosing not to go.

We need to look at how we design our hospitals and healthcare systems going forward to accommodate this shift and the information and how we exploit that will be king on working out how we go forward with a healthcare system that’s fit for purpose after this.